Among the many elements that Alkov et al [2] describe, there’s a common factor applicable to every staff involved in the air industry: training…

– By honing flying skills

– By taking care of personal health and attitude

– By applying crew / team resource management, using updated terminology (CRM / TRM)

– By using briefing / debriefing techniques

– By supervised exposure to ground based simulations, followed by in-flight situations, where the pilot and controller gain expertise for risk management, dynamic problem solving, attentional control and experience.

– By turning cognitive judgement into perceptual judgement, which is almost automatic. The more perceptual the judgement is, the bigger the margin to address unexpected situations.

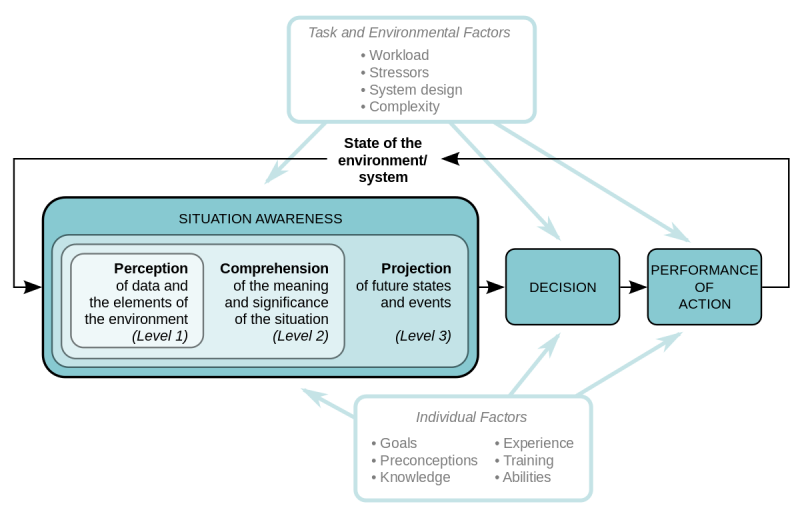

This line of reasoning leads us to the field of “Decision Making”, where we have:

– Classical or normative Decision Making: training on the ground and in flight, starting with a theoretical background of data and information.

– Naturalistic Decision Making: where the crew utilizes the schema of a given prototypical situation (real or simulated to draw the long term memory and yields an almost spontaneous response to the identified/recognized situation.

Again, at the end of the process by making a decision, training turns out to be fundamental. We can develop our ability to improve situational awareness through preparation and planning, and that’s probably the biggest point we need to concentrate on is…

How do we do this?

References

1. Jensen RS, Guike J, Tigner R. Understanding expert aviator judgement. Chapter in Decision making under stress: Emerging themes and application. Flin R, Salas E, Strab M, Martin L (Editors). Aldershot:Ashgate, 1997: 233-242

2. Adams MJ, Tenney YJ, Pew RW. Situation awareness and the cognitive management of complex systems. Human Factors 1995;37(1): 85-104

3. Endsley MR. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Human Factors 1995; 37(1): 32-64

4. Endsley MR, Kiris EO. The out-of-the-loop performance problem and level of control in automation. Human factors 1995; 37(2): 381-394

5. Orasanu J. Stress and naturalistic decision making: Strengthening the weak links. Chapter in Decision making under stress: Emerging themes and application. Flin R, Salas E, Strab M, Martin L (Editors). Aldershot:Ashgate, 1997: 43-66